Tending to Emotional Basic Needs in Grief Counseling with SCARF

SCARF is an acronym that sums up basic social needs:

- Status

- Certainty

- Autonomy

- Relatedness

- Fairness

SCARF, a Short Introduction

David Rock defines the five terms in SCARF as basic needs, and successful communication is based on respecting them:

- Status means recognition by an outside party or counterpart.

- The second factor, Certainty, describes a sense of security that results from predictability.

- Autonomy Autonomy describes a person's ability to achieve something with their own means.

- The fourth factor, Relatedness, refers to the feeling of being connected, of community.

- Fairness describes to the individual sense of justice.

Each of these needs can take on different facets and forms. What they have in common is this: For all their individual variation, everyone wants to see their basic needs met while interacting with others.

In conversations with bereaved people, the SCARF model helps me to assess how I can strengthen basic social / emotional needs of a bereaved person to strengthen the overall stability and help with coping.

The underlying aim is to offer a bereaved person stability and help them regain a sense of agency.

Supporting a Bereaved Person with SCARF Factors

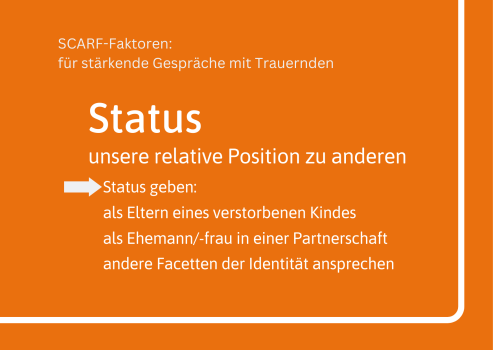

"Status": Strengthening One's Identity

Status is described by Rock as “our relative importance to others”. In conversations with bereaved people, this aspect draws my attention to the fact that a building block of identity can also be lost with the loss:

Am I still a daughter after the death of my parents? How can I live as a sister or brother after the death of my sibling? And for someone grieving for their health, the question could be: Who am I, if not one with the sporting, healthy lifestyle?

Losing a piece of identity or a role, we were firmly settled in, can lead to a situation where we lose a part of our feeling of self-importance. That in turn can nibble at our perceived status, understood as the “relative importance for others”.

In conversations, the first step is to acknowledge this secondary loss: “I can hardly imagine how strange this feels right now.”

Secondly, I address a person by that lost facet of their identity as long as they are open to it: Seeing someone as a sister or brother even after the death of a sibling can help them to navigate the new situation, as their threatened role is safe with me.

Only if the bereaved person is open to it and stable enough, I work with the part of the identity that is perceived as lost. In my volunteers work with bereaved parents, the question of “How am I a parent” is common. The aim is to find options for a new relationship. With a health-conscious woman who is undergoing cancer treatment, I look for existing knowledge about health or her body that helps her get through this. This means changing the form that this part of their identity takes.

As the conversation continues, I actively pay attention to other facets of identity and address those roles as well, to support their feeling of “status” within their world.

- Oh, you're a teacher. That is a role with lots of responsibility, isn't it? What is it like for you?

- You like gardening? What is your favorite part? The planting, the growing, or the harvesting?

- What do you like about your job/hobby/neighborhood?

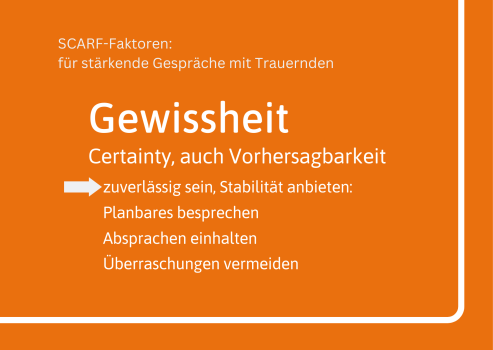

How Bereaved People Can Recover a Sense of Certainty

The more unexpected you are hit by a stroke of fate, the more it may challenge life's certainties. And no matter how old someone is: The death of a loved one is quite often experienced like that. Death is, in a way, the ultimate is loss of control. That can lead to a situation when mourners feel like people to whom things happen, perhaps even as victims. As a result, they may lose their ability to act and their sense of agency.

Most bereaved persons automatically recover from that loss of certainty over time. If their environment offers and provides stability, this is a very effective form of external support. Starting with simple things such as “being on time” or getting in touch on Wednesday evening when you said you would. In connection with emotional support, stability goes a long way towards bearable grief.

Surprises, on the other hand, are not always perceived well by a newly bereaved person. A surprise birthday party 10 months after the death of a partner is certainly well-intentioned—but can add to the sense of "not being in control", and diametrically opposed to how the bereaved person feels about the day! A conversation beforehand helps to take the wishes of the mourners into account.

A secondary aspect that indirectly strengthens lost certainty: To experience the ability to cope and regain a sense of agency is extremely helpful to appeal to one's own ability to act. Which brings us to the third SCARF factor: Autonomy.

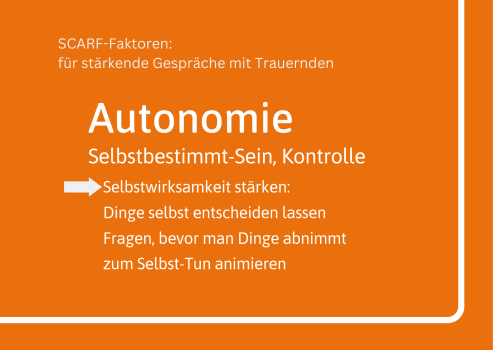

My Favorite: Strengthening “Autonomy”

Autonomy is something that we can very easily and early support in grief counseling: It involves encouraging a person to make decisions and do things themselves.

And that is very difficulty sometimes for those around a bereaved person: Many people's first impulse is to help as much as possible for the bereaved, from housework to organizing the funeral service. After all, you do want to help.

However, it is usually more helpful if a grieving person experiences themselves as agents who, in view of their powerlessness in the face of death, can at least influence the issues that are now pending. For example: Which coffin? What music? And in their everyday situations: What and when do I want to eat?

My advice to people around bereaved persons: Ask mourners actively to make the decisions, even if you take care of things for them. Ask them explicitly what they would like to do and what they would like to do themselves. And for more complex issues such as telephone calls to the authorities, offer to do this together . Thus, you are supporting them and at the same time, they regain confidence that they can influence things, decision by decision.

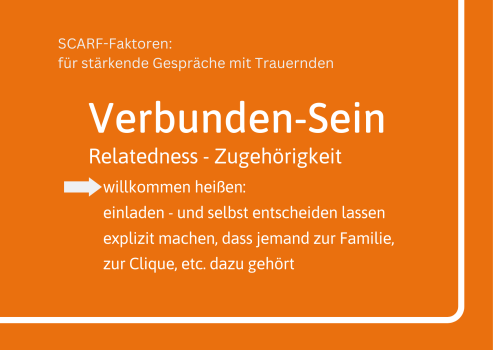

Relatedness: Finding Strength via Belonging

Strengthening a grieving person while working with Relatedness as the fourth of the SCARF factors means establishing a sense of belonging. They can find that with friends and family, and they are unintentionally part of a community of people who have also lost someone. Meeting these people, for example in a grief support group, is helpful for many people in mourning. Here, many bereaved individuals express a feeling of closeness, acceptance, and of feeling understood without the need to explain. (Article on Grief Support Groups - Trauergrupppen - in German only).

People looking to support a grieving person, from wider family, friends or in a professional context, can easily leverage the need for relatedness. E.g. by continuing to invite a widow to game evenings or picknicks, they all shared as couples before. One addition is helpful: “Do come - and please feel free to decide spontaneously”.

This shows the grieving person that they can make ad-hoc decisions depending on their reserves of strength and needs.

I do the same in support groups: I ask the participants to ask themselves on that day if they have the strength and openness for our conversation or the group session at the agreed time - and to cancel if it is too much just now.

The Most Difficult SCARF Factor for Bereavement Counseling: "Fairness"

Fairness is difficult to find when facing difficult situations or losing someone close. To be honest: of all the SCARF factors, fairness is probably the one that can hardly be strengthened directly. There simply is no good answer to “Why me? Why us?” when a loved one just died, when we face a harsh diagnosis, or when are struck by another figurative lightning. In conversations with people of faith, the belief in a superior power can be comforting. And it can also be a burden: “How can God allow this?”

Many grieving people feel comforted when we acknowledge that their sense of justice has been violated: “No, that's not fair.” Or: “No, nobody deserves that.” Finding meaning in a death, or at least not being consumed by the lack of meaning, is one of the most difficult learning tasks for mourners.

For someone supporting a grieving person, this includes (unfortunately): Accepting my powerlessness first. And as unsatisfactory as this answer may seem compared to the tips above*: Finding the stamina and patience to face something we cannot change sometimes is the most precious gift we can bring to a conversation in a difficult situation. Coupled with an open heart that hears and takes the other person's needs seriously, the ability to bear with them and their situation is the basis for a strengthening, helpful conversation.

Indirect reinforcement can be provided by actively emphasizing when a bereaved person later (or in another conversation) talks about what they had, when they bring back fond memories or are grateful for the time they spent together. This helps towards the “search for meaning” or "meaning making" (article in German), a concept by Robert A. Neimeyer.

*I am notgiving up on fairness: If anyone has any ideas for wrangling with fairness, I'd be happy to hear from you: mailto:hallo@trauer-coaching.de

Strengthening the Sense of Agency with SCARF Factors

(Please click on graphic to see English version - and sorry for the hassle)

I already mentioned the effect of having a sense of agency. For me, this is the secret magic formula in conversations with a bereaved person. It is also one of the factors in resilience. Sheryl Sandberg shares wonderful insights on this in her book Option B on resilience and grief.

Compared to other resilience factors such as optimism or solution orientation, I find it relatively easy to effectively support regaining a sense of agency even in acute situations.

The examples above are suggestions as to how resilience factors as sense of agency and network orientation can be supported with the easy-to-remember formula of the SCARF factors.

How do you work with the SCARF factors? Or which other concept do you leverage? Let me know: mailto:hallo@trauer-coaching.de